Welcome to carnel Issue 15. This issue is a themed one that attempts to concentrate on Noir-y topics and ideas and applying them to RPG's. Since I have recently been running a noir style fantasy game in the Greyhawk setting I have decided to write up my notes on this game and, hence, the subtitle Greyhawk Noire

.

On the administration side of things the great subscriber cull has proved a great success carving the subscription list down to about four or five addresses. A size that is far more manageable I think. On the transition from paper only to web and paper publishing I am not so sure of the results.

You may notice that there are no zine reviews in this issue. There are two real reasons: firstly we did not have enough zines to form a sizable review. Secondly there is the potential that this issue might be handed out at Dragonmeet and as Tim Eccles points out with every zine review carnel loses another reader. Now normally that is no bad thing but I do not want it to happen while I am still in the room.

Rest assured though that Man & Moose will return in the next issue and will hopefully be spitting tacks as normal; enlightening and infuriating in equal measure.

As an experiment this time around I am going to shamelessly steal an idea from some of the American APA's we have kicking round the place at the moment (holdovers from the zine review section). Basically the "theme" of the next issue (in so much as it will have a definite theme) is "Greyhawk Nights" a collection of Noir themed FRPG scenarios focussing on Greyhawk but covering anything on the edger side of life.

If you have any thoughts on the matter send either a letter in to Monkey's Place or preferably send in a scenario, cameo or even campaign outline.

Until the next time.

Victorian Villainy

© 2000 R. Rees except where otherwise stated.

Cover image © 2000 E. Collins

Top Floor Flat

22 Victoria Square

Clifton

Bristol

BS8 4ES

Address valid until the end of 2000.

carnel@talk21.com

http://www.geocities.com/shudderfix/carnel

The subscription address is the same as the editorial one given above.

Please send five (5) US Dollars per issue or the equivalent value in any currency.

Rats! No subliminals.

Wizards of the Coast have recently kicked off an unusual and confused scheme to provide "Open Gaming" with their newly revamped d20 system (the basis of the new Dungeons and Dragons edition).

Basically the idea is that what roleplaying really needs right now is an "Open Source" license. You know; like the computer operating system Linux. This is not the first time that computer licensing has been held up as a model for roleplaying. Popular generic RPG system FUDGE has often been held up as an equivalent to the computing concept of "shareware". Why the computer industry now possesses some vital cachet that needs emulating is not clear.

In a nutshell the idea is that WOTC will "Open Source" the mechanisms of D&D 3e (funky Internet speak for 3rd edition). Other companies will be allowed to use the ideas in a subset of the system to produce their own versions of D&D or simply supplementary material such as new classes, skills and so on.

What does WOTC think they are getting out of an "Open Source" concept? In some ways the logic is understandable, tacitly such a license already exists between roleplayers and commercial RPG manufacturers. To help spread the word about a games system many companies tend to look to devices such as magazine published scenarios that offer some convenience factor, for example providing complete statistics and game data. The use of the technical jargon of the game, its attributes and mechanisms, is taken for granted for otherwise how would people be able to share ideas and concepts about the game in a common format?

The confusing aspect of this is how it ever came to pass that only people who owned the trademarks for a game could write for it? Is not the "Open Gaming License" simply giving gamers back something they already had, or at the very least deserved?

Game concepts such as HP, XP, monsters and skill checks form the very jargon and argot of RPG. Trying to control it legally is farcsical. Trying to control the language of RPG is trying to close the stable door after the stable has collapsed of old age and the horse was long turned into dog food.

Beyond the actual technical terms there is the equally vexed issue of who actually owns RPG ideas. The problem is created by the oral nature of RPG's. As an example, if I play in a particularly enjoyable game at a convention and then decide to try and re-run the game for another group later am I breaking the law? Obviously the game will not be exactly the same, in the transition from player to GM there are subtle changes of style and substance. The ideas mutate as they move along - just like myths and legends. Who owns the result? Can they license it?

The Open Gaming License may be spin but it is opening the gates to a serious discussion of who owns what in the RPG world and beyond that what counts as "property" in a hobby that is based on co-operation and collaboration.

I am not much of a fan of the Discworld novels as I have pointed out in this fanzine before. Therefore fans of El Prachettismo might feel that there is little point in me reviewing anything associated with the ever more exploited Discworld. Well you are probably right; except that Discworld Noir is the closest the Discworld has come to being funny in quite some time. Its biggest advantage is that the authors have decided to include a heavy dose of film noir pastiche and parody rather than relying purely on "zany" Discworld jokes. The pastiche comes from an almost verbatim lifting of the plots of The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon. The parody comes almost entirely from the ironic appropriation of those films dialogues and then transposing them to ludicrous situations in a fantasy world. Yes this game is just one big postmodern fucking nightmare. It is also what Pratchett did in the Colour of Magic

where he successfully sent up the fantasy genre novel.

All of the pastiche and parody is good as the more traditional Pratchett humour mostly falls flat. Talking dogs, characters constantly pointing out that the river has a crust, sailors with fake accents, wizards with pointy boots? If these things make you laugh then I have to pity you.

It is a sad testament to British arrogance that we often claim that the Americans have no sense of humour. A shame when the American games industry managed to produce the hysterically funny but also dramatically satisfying Grim Fandago in the same year that their British equivalents put out this underdone turkey.

As a testimonial to the lack of imagination of the games producers (as well as their tendency for wholesale appropriation of dialogue) I noticed that at a certain point in the game one of the characters (a wizard fixing to end the world) suddenly quotes verbatim Davros' speech from the "Genesis of the Daleks". Was this a cunning reference that I should find hilarious secure in my fanboy knowledge of British sci-fi, or is it just a tedious replacement for some genuinely amusing banter in the Lucasarts style?

Comedy is often one man's meat and anothers poison; suffice to say that at points DN was so unfunny it made you want to die while at others it did manage to raise a laugh. What it failed to do though was involve you enough in the game and provide enough straight

material to balance the humour. Kind of like Costello without Abbot.

Its main failing though is in separating the player from their on-screen counterpart. 50% of the gameplay was spent not investigating the mystery or laughing at the jokes but trying to get your on-screen counterpart to realise what had become completely obvious to you, the player.

The high point example of this came when a choice of two locations becomes available for a murder that is due to happen. A cursory examination of one reveals human bones picked clean which indicates that whatever happened here happened some time ago. Hence the other location must be the spot. That simple though? Not at all, to be "allowed" to stake out the other location it is not enough to find the bones. First you have to get a leaflet from the theatre, use it in a library to get a list of books, read the books to get a list of clues, go back to the wrong location, use a clue on a shop sign, use a clue on the bones. Intuitive detective work? Hardly, not only that but can I blame this basic programming and testing incompetence on Pratchett? No, damn it, for better or worse his involvement here was minimal.

In the end I was left with mixed feelings for DN. I certainly did not find it funny but it was a diverting adventure with a very good mystery at its heart. Unfortunately the game (particularly with its linear structure) did not really allow the solid underlying story to be revealed. Most of the time was spent trying to get your character to understand what you as a player understood yesterday. Partly this lack of satisfaction lead to the idea of Greyhawk Noire, proving that at the moment the genuine human roleplaying experience is very difficult indeed to replicate on a computer. In saying this though it seems clear to me from my experiences with Grim Fandango, Monkey Island and even Broken Sword that this breakdown in communication between the game and the player is not necessary or unavoidable. Time and effort is well-spent on a good interface and in testing whether the milestones of a linear plot are correctly spaced and positioned according to the effort spent in achieving them.

Given more talented people writing the software for the game and a lot more QA work on areas where the linearity of the plot is simply a hinderence rather than a necessity could have resulted in a truly absorbing experience.

As an example of what did work in the game the background art was truly gorgeous. All unfortunately displayed at a criminally low-resolution (with lazily no option to hike it up) though. The opening scenes at the detective's office, then the docks, followed by the first appearance of the seedy gin joint Cafe Ankh were wonderfully evocative. The enjoyment of watching the 'tec walking up to the neon sign of the cafe through the rain with lighting crashing around the twisted wooden rooves of the city was an experience sadly unmatched in the rest of the game. It was an indicator of what could have been achieved here if enough effort had been committed though.

There is an opportunity here for a Discworld Noir II but the developers will need to put their backs into the work to avoid another half-hearted lacklustre effort like this. I think they will need to look hard at their competitor's games and discount the attraction of the Discworld brand name. If there were no marketable Pratchett elements here, would it still be a good game? If the answer is an unqualified Yes

then more power to them.

The Forgotten Futures (FF) RPG series is dedicated to all forms of Victorian-influenced roleplaying. From the vaguely realistic to Steampunk

, from the science-fiction of Jules Verne to the Boys Own world of Fu Manchu, FF aims to re-create them all. The series as a whole is an admirable and, in some areas, an alarmingly involved act of dedication and obsession.

One of the goals mentioned in the introduction to the FF CD-ROM collection is that the game will keep the stories they are based on alive

and provide these period romances with a new audience. There is more than a touch of the romantic in that goal let alone the stories the project aims to preserve.

In addition to preserving obscure Victorian novels that have lapsed both out of print and out of copyright the FF collection also includes a selection of period magazine and newspaper articles and indeed any relevant illustration, snippet or piece of prose the author can lay his hands on.

This noble aim of reviving a forgotten part of British literary history aside though, FF is still a game and all games, if they are to survive, must be played rather than admired for their principles.

The heart of the Forgotten Futures system are the core rules for playing Scientific Romances. These rules deal with the the classic RPG topics: combat, injury and healing, attributes, skills, making checks and earning XP.

The system is simple and stripped down - it would seem that the rules should not get in the way of the game. This seems right, after all we are not dealing with a simulation here but a recreation of a style of literature. In this respect perhaps the game is soft

rather than hard

science fiction but the difference is in our perception of the rules of science compared to that of our predecessors over a hundred years ago. There is a logic at work here but not the one of quantum physics and microprocessors.

Characters have three attributes and the skills are chosen from a list of twenty five that seem to cover the bases in surprisingly comprehensive way. Anything that is genuinely not covered by the skills can be caught in the attributes as though they are few in number they are correspondingly broad in scope.

Combat is carried out via skills and wounds are recorded in a fashion that reminds me strongly of the Indiana Jones RPG (the TSR not the WEG version). Each character has a number of wound check boxes. When checked these wound boxes inflict a penalty on all rolls made for the character. If a wound box needs to be checked again (i.e. a wound of the same severity is dealt again) then the next most severe checkbox is checked instead - incurring bigger penalties and moving the character closer to death.

Dice rolls are made on the conventional 2d6, something important for the casual or first time roleplayer. Too often games seem to assume an arsenal of paraphenlia is available to the potential player or GM: Everway's cards for example, but a d20 is just as valid an example. It is nice to see a game that can be played with a twenty page printout an a pair of dice swiped from the family Monopoly board.

The twist

on this essentially conventional rules setup is the addition of the Worldbooks

. Worldbooks add, change or twist the core rules according to the specific requirements of the background genre that is also described in the Worldbook. The idea is not necessarily new but Forgotten Futures is the first I have seen to do a satisfying job of it. It is like a supplement - except it works! Rules are introduced with, and because of, the background to the setting; the background is introduced with the rules that support the kind of game that can be played in the setting.

Each of the six volumes of FF has a different Worldbook but the same core rules. Thus each supplement for the game introduces very different subjects and styles of game but in an extremely economical fashion that keeps the basic ideas the same.

I must admit to not really getting

FF before now. A number of individual ideas seemed interesting: the American Civil War fought with Zepplins, the disasters collection, a Victorian version of the Channel Tunnel, the electric pentagrams of the Ghost Story supplement. Despite this overall I simply was not connecting with the setting.

Fortunately, or maybe unfortunately given the topic of the sixth FF supplement Victorian Villainy

, the latest release has been something of an epiphany. Sherlock Holmes, Fu Manchu, Bulldog Drummond; I get. I see how a game featuring a Holmes-like character might play out. As a fan of the Alan Moore comic book serial League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

I also see how the pulp of the Thirties can be mixed with the mystery and thriller novels of the 1800's to produce an exciting two-fisted tale with a weird science twist.

Having finally found a hook

into the system I was glad to finally get a playtest underway. One of my first mistakes though was failing to understand the relation of the Worldbook to the Core Rules. One particular problem I was having was the fact that during fights the heroes never seemed to be able to knock anyone out and instead ended up hideously wounded after any fight. The two-fisted tale

nature of the game was at risk because the players' concern for their characters survival meant they were understandably bent on tooling up with the biggest firearms they could buy. I was on the verge of e-mailing Marcus and asking him where I was going wrong when I finally noticed a small section in the Characters part of the Worldbook that dealt with my problem exactly.

any unarmed blow which strikes a henchmen ... will automatically cause a knock-out

In my defence I did find a lot of this particular Worldbook slightly confusing as it packages together the rules for two very different styles of play: Heroic

or Melodramatic and Anti-Heroic

, which covers slightly more earthy adventures. Since I was ignoring a great deal of the Melodramatic style of play it was not always easy to pick out what modifications did or did not apply to the kind of game I was running. I think it may have been worth splitting the two styles out more comprehensively in the book. Or maybe I should have read it completely and ensured I understood it before I tried to run it.

It also took me a long time to understand the mechanic of the Core Rules which is odd because at its heart it really is quite simple. As mentioned before the game is run off a 2d6 mechanism. Most checks (attribute and skills rolls) are based on an opposing pair principle. The Attacking Value is the score of the relevant Attribute or Skill for the character who is attempting the action. The Defending Value is either another attribute or skill score if the action is directed against or opposed by another character (or NPC). Otherwise it is set by the GM to reflect the difficulty of the task. I routinely used a 5

for an average difficulty but I understand from the rule book that a 7

might be more appropriate.

The Defending Value is subtracted from the Attacking Value and the resulting difference is applied to a base number of seven. The player then rolls the dice. If the dice come up with a number less than or equal to the target then the check is successful. Otherwise the roll has failed.

As an example, if I have a Drive skill of 4 and I want to try and take a corner at slightly higher than the manufacturer's recommended speed then the AV is 4, DV is 5; the difference is -1. 7 - 1 is 6 and therefore I need to roll a six or less on two six-sided dice. In practice this seems impossible and I believe I may have started off with the wrong number of skill points when the characters were generated. As it is they seem to be constantly failing more rolls than they pass.

Again in defence of the system and to point out the failings of the reviewer the rulebook does state that a character with any ability with a skill should not have to roll for mundane and routine tasks. Still, given the style of play there is not much of the routine and mundane to begin with - so what happens then?

The mechanism reminds me of Traveller. However what seems to work in that system seems unsatisfying here. The Attacking and Defending Values have some advantages, notably in the ease with which they allow scaling

of the mechanism from fist-fights to barrages between sky-ships, but seem unnecessary and fiddly on the smaller human scale. The scale, it must be said, on which the majority of the game takes place.

The creation process also has a neat mechanism where the three basic attributes (physical, mental and spiritual) combine to provide the base scores of skills. Unfortunately the relationship between Attributes and Skills is not intuitive and simply has to be looked up every time. It also creates a situation where it seems more sensible to put as many points into your attributes as you can and then simply put one point into the skills you want. Your high attributes will then give you high skill ratings for what seems like a minimal cost.

Maybe that is the intention but I noticed that min-maxers took particular delight in trying to break the system.

The first game was a particularly good cunning scenario from the supplement called Wheels of Terror

. Unfortunately the players approached the whole jaunt far too conservatively being used to less forgiving genres. A few appalling failures on their skill rolls and the whole thing degenerated to the point where not only had they failed to unearth the villain but half of them had been arrested and the other half did not have a clue what was going on. As a result they let the whole dastardly plot unfold because they did not realise there was a dastardly plot afoot!

I suppose that as the GM I was mostly to blame here. I was not comfortable with the system and not really sure what you were meant to do in this genre if the heroes give up on the whole thing and end up going down the pub (metaphorically speaking).

For the rest of the playtest I decided that having become slightly more familiar with the mechanic of the game that I would wing most of the rules and try to keep the excitement level high and page-flipping low. I have also decided that linear plotting is in some respects the way to go with these pulp style games. Since you are trying to outwit the master villain there are not always a great many choices as to what you can do. Essentially the villain forces the pace of the game until they are uncovered and the heroes have a chance to decide how they are going to foil the villain's plan.

So far this seems to be working out and the game seems to be getting better. Certainly the players have shifted from merely indulging me in a whimsy to congratulating one another whenever a major plot twist is successfully uncovered and firmly dealt with.

As a final point for the preview I would say that I appreciate the amount of work that has gone into researching the Worldbooks. The effort really pays off and I can easily say that if any of the genres or periods are of any interest to you either as a GM or a player you could do far worse than buy a copy for the background alone.

The obvious way to start with Forgotten Futures is to take out a subscription that entitles you to the CD-ROM collection of the various Worldbooks (as well as the rules themselves).

The CD-ROM can be ordered, at a cost of £10, at the following address: Marcus L. Rowland, 22 Westbourne Park Villas, London, W2 5EA

A company called Heliograph are committed to producing a normal paper edition of the game that you should be able to order via your local store. Heliograph's webpage is at www.forgottenfutures.com. A booklet edition of the rules was produced for issue 19 of the the now defunct RPG magazine arcane, you might be able to get a copy second hand.

Marcus has been kind enough to send me an extra CD-ROM of the Forgotten Future settings 1 to 5. I imagine he must think I am horribly corrupt for having held onto it for so long so here we go with the first carnel competition. Send the answer to the following question on a postcard (I do not want to fill my e-mail box up with countless messages all saying the same thing) to the editorial address. The winner will be chosen at random and the CD dispatched to them post-haste.

The question? Who was Fu Manchu's dogged nemesis?

What could have resulted in me purchasing such an awful little trashy game novel? Was it the long flight back to the UK from America? Was it curiosity given that I was starting to have ideas about a detective style fantasy game? Was it simply that I have no taste and rather than chose some life-enriching book in a unfamiliar book shop I always opt for the fantasy equivalent of Bridget Jones?

Whatever; let me be frank - I like trashy fantasy novels, particularly ones tied to RP game worlds. I read the Avatar series, I thought they were okay; I read the Prince of Lies novel I thought it was quite good. I read Murder in Tarsis I thought: take this lame dog away and shoot it, along with the hack who brought it into being.

Here is the pitch: a diplomatic representative of a nomadic horde laying siege to a corrupt city of merchants (whose city defenses have been ruined by an earlier earthquake) has been murdered. With the nomads poised to sack the city in revenge, two fast-talking misfits have to find the killer and try to avoid being bullied by their employer into pining the murder on an innocent rival.

Sounds pretty good and a pretty hard thing to get wrong. All you have to do is keep the style terse, the action moving and the revelations arriving. Agatha Christie could have done this in her sleep.

Unfortunately there are a series of tragic errors in execution. Firstly the characters talk in game terms, example: "Falling under a geas is far from the worst that could have happened". Secondly no time is spent building up the characters or dealing with their relationship. Early on the fighter hits the thief/assassin with a geas spell and they end up like Nolte and Murphy in 24 hours, an odd couple with a case to close and quickly. Only without humour, or the excitement, or the personality. The pair of them swiftly move to exposit their backgrounds through tedious page after page. Such a clumsy unravelling of the characters' past is at the expense of their current feelings and leaves the reader thinking so what?

Ten minutes ago they were trying to kill one another, now one spell later they are best of buddies, tell me how that feels. Show me how they suddenly change. Do not just tell me it has happened.

Thirdly, sidekick: apparently all groups in RPG based novels have to have them. Here it is a completely unsassy, unstreetwise, thief/urchin/orphan who later falls in love with a barbarian. She would be utterly unbelievable except that she is accompanying two characters with all the plausibility and depth of a pair of cardboard cutouts.

Which leaves the mystery, do this unlikely duo unravel the mystery and reveal all? Well - no not really - they bumble around, guess that all is not well and eventually a deus ex machina ending is constructed by throwing a few spells around and one of our heroes

discovers that the killer is his old childhood friend! Given that the killer's disguise seems to consist of only a pair of magical contact lenses one does have to wonder what kind of detective we are dealing with here.

Well probably the same type as the kind of novel we are dealing with here: the worst.

Recently TSR/WotC re-released some of the classic AD&D hardbacks as tiny mini-books, akin to Penguin's anniversary £1 classics. I picked up two from the London gaming store "Orc's Nest": Oriental Adventures and Greyhawk Adventures (GA). The former reaches anywhere between £50 - £90 so if you see it cheaper you might as well buy a speculative copy. The latter, like most early Greyhawk material, I have not seen in any kind of decent condition so I was happy to part with my fiver for it.

The books are exact replicas of the original only one-seventh the size or some similar aspect. I had to give up reading them raw without the benefit of spectacles or a magnifying glass as the text is just far too small. Fortunately as a facsimile these books are identical to their previous incarnations down to the artwork, text and typos.

GA is one of the old style RPG supplements, it does not really have a theme or a concept. It is more a collection of oddments from someone's campaign notes. There are sections devoted to new monsters and spells, old staples that hardly seem necessary these days. More bizarrely, and importantly from a GM's perspective, GA has a detailed description of a lot of the Greyhawk gods and religions. This material is recapped in the new Greyhawk books but not in the same level of detail making GA a necessary purchase for prospective Greyhawk GM's if they are to understand a lot of the references in the newer books.

The same goes (but to a much lesser degree) for the section here on notable NPC's. The reason this section is not as important as the piece on religion is that most of the NPC's were revised or updated during the Greyhawk Wars. The only importance this has now is for referencing former residences and businesses in Greyhawk itself.

There is a chapter on "Geography" but this is a bit misleading, really this is a collection of "interesting places" that PC's might visit. Like the "adventures" section this is really an extended list of scenario seeds and campaign anecdotes and rumours. While several of the places and ideas have been expanded subsequently in later books (notably the Pits of Azak-Zil) none of the material is really must have.

To sum up a short review of a little book then. Pieces of perfectly reproduced gaming history that verge on the status of memorabilia. The mini-books are a nice idea and astonishing replicas (down to giving the old addresses of TSR US and UK!) but while I like the format I could have done without the miniscule text which makes an otherwise extremely portable book into an annoying liability in the low-light world of most gaming tables.

Shadowrun is one of those games that proves that we have reached the end of history and that from now on we are idiot savants assembling the future via pastiche, recital and parody of the past. An unsubtle blending of D&D and Cyberpunk the concept cannot be truly said to go much deeper than the rough Eureka of "Orcs! With guns".

Despite this, Shadowrun is not devoid of interesting ideas. Its background posits not so much a figurative as literal "archaic revival" where a rise in some kind of arcane energy level leads to the re-emergence of not only magic but all manner of fantasy races as well. Apparently humans are the basic template for all life in the universe but when exposed to magic they turn into different genetically distinct species. Sort of like Gremlins then; but not as imaginative... or amusing... or entertaining.

The background is utter tosh then and acts only as a thin veneer to move onto the real meat of the matter. D&D with guns, computers and motorbikes. If you think that perhaps I am being too harsh, well, apologies but the game's publisher FASA seem to agree with me as well. Shadowrun Quick Start Rules (SQR) spends exactly one page on the background out of sixty-four. Combat, by comparison, gets eight; Equipment, five.

So our basic parameters are set and whether you like it or not is irrelevant, the question is: given the ludicrous basic idea how well does the game pull it off?

Well for that particular answer you are going to have to buy Shadowrun: The Third Edition because (and from here on in the knives come out) these "Light" rules fail almost completely to give you what you need to play a 21st Century Elf with an attitude and a .44 to back it up.

According to SQR the future will not use money as despite having an equipment list, none of the items actually have a price. Now a lot of games can get away with this, they either abstract the idea of money and resources ( Vampire) or they assume that characters can have anything their players want providing it is reasonable given the background of the character ( Forgotten Futures). The major problem is that the Cyberpunk genre is inherently wedded to consumerism and the fetishisation of both commodities and consumption itself. Having no monetary system blows a major aspect of the genre out of the water, money more than morals or a political agenda motivates the 'punk protagonist.

This failing leads me into another problem with SQR's vision of the future in the form of the utter lack of branding. The stores of the future will sell a Medium Pistol or a Cybernetic Eye. While this is admirably honest compared to our own era of brand loyalty and lifestyle goods it is utterly implausible and out of keeping with the genre the game is meant to be reproducing (well, assuming that FASA actually did want a Cyberpunk element to the game).

At this point someone who liked SQR might point out that all these flaws could be put right by a good GM: set up a basic price list, currency, some corporations and some brands culled from cyberpunk books or comics. Of course a good GM with a good deal of free time could do it but then they might as well push on a bit further and write a basic combat and magic system and save themselves the cost of SQR so what are we saying here?

Unlike most mini-rules and introductary systems SQR does not appear to know what it is trying to achieve. GURPS Lite for example is introducing a rules system, the White Wolf "Quickstart" series concentrates on an adventure that allows an exposition of the game background and hangs the rules around what is needed to run the adventure. SQR seems to aspire to something between the two, it introduces a rules system but it is a rules system that is informed by the background of the game that is being run. Unlike R. Talsorian's Cyberpunk the full game makes no pretence of being generic. The magic system makes clear that there is a definite background in mind when it starts banging on about Totems and Native American magic styles and beliefs. By holding back on the background though the game is selling the potential purchaser short. If they like the initial game when they do move to the full blown Shadowrun then they will have to transition to a background that is only hinted at in this book (and sometimes not even that). Someone who purchases this book would seem - to me at least - to be interested in Shadowrun but the answer to their questions seems to be "Not until you pay us another sixteen quid."

It seems impossible to recommend SQR as it seems almost impossible to play it. I have to admit that the sparseness of information in the book lead me to forking out £3.50 for a second-hand copy of the Second Edition. While I probably had a good deal I cannot say that any game I subsequently play with SQR is any kind of realistic example of what you can achieve with that book alone.

For me at least, it is does not have enough depth and I am not talking just about the background here (the rest of the review is about that). The whole issue of the Matrix (the 'Net) and regular skill tests are side-stepped rather than tackled. The system is not that simple (d6 dice pool system against a target number) and the brevity and lack of clear writing on the basics makes the more complex sections on combat and magic more confusing that they should perhaps be.

The system also completely fails to show how you can create your own character rather than using one of the templates provided at the back of the book. This seems the worst omission to me. It shows how limited the fun you can have with this book is. It does not even include a character sheet. You are meant to pick a pre-generated character, read the descriptions of the bits of equipment and spells you have been given, play the introductary adventure and then? Well then you buy the full game of course.

Most FRPG's cities are often nothing more than the projection of a modern idea or ideal onto a pseudo-medieval background. Often magic takes the place of technology but the urban culture is lifted verbatim from the real world into the "fantasy" equivalent. Policing, hygiene and government are all recognisable modern. Except; except more often than not these urban environments are extremely idealised. Not for our fantasy world the idea of urban decay or poverty not even the mud and muck of the "historical" city dweller. These cities are the cities of our imaginations freed of the tiresome "facts" of a reality that often disappoints.

Now I don't think there is all that much wrong with this. In fact RPG environments are often a "safe" place to expound personal theories or play with "dangerous" ideas and situations. The trouble is that the city becomes a neutered creature devoid of the tension and excitement of its real world counterpart.

When I saw a new edition of Greyhawk I was excited at the possibility that one of the more famous cities in RPG might have finally received the treatment it finally deserves. I had enjoyed reading about Carl Sargent's vision of Greyhawk in his Wars and Ashes series. What had held it back though was the fact that the requirements of space meant that Sargent frequently referred to the boxed set The City of Greyhawk that was out of print by the time I had started to get interested in the subject. I hoped that the new book might cover the gaps.

I was disappointed though - while Sargent had envisioned a late medieval, early Renaissance city not unlike the diplomatic and commercial hub of Venice the new authors pictured a more conventional city (a vision with a certain amount of similarity to the "modern world with orcs" portrayed in Greyhawk Adventures (see review later)).

I was disappointed but there was still a lot of information in the book and more than enough to run a couple of sessions in the city. However given that there was nowhere near enough information to play a "culture" style game I needed to do something a little bit different. The problem with the conventional city FRPG campaign is that there is none. The city is always a fleeting backdrop to the scenario. What I wanted was to effectively make the city a "character" in the game as much as the actual NPC's are characters. Whatever makes Greyhawk Greyhawk had to suffuse any game I was going to run.

In this issue I've listed a lot of the influences on the game I ran in the form of reviews. In this article I hope to explain how they all came together to make for a different take on a fantasy city.

Primarily the idea of running a Noir style FRPG came about by playing two computer games: Thief and Discworld Noir. In terms of feel Thief is the more important of the two but in visual terms a lot of the artwork for Discworld Noir was superb. The idea of a traditional fantasy city shrouded in night and burdened by a never ending hail of rain through whom's drizzly mist shines a "neon" sign spitting magical sparks really struck a chord. If it could invoke a strong impression with me then surely it would do the same for my players?

Of course image is not everything and here Thief comes in with the laconic world-weary monologue of it's main character Garrett. Where as Discworld Noir often seemed to be aiming at simply spoofing the images of Noir rather than the conventions of the genre and often doing that in the most childish and superficial way possible Thief took itself seriously and therefore could create a dark angry character in whom greed, principle, self-interest, duty and revenge created a dark sea of conflict from which arises the anti-hero. DN's protagonist on the other hand has all the outward symbols of the Noir PI but utterly no motivation other than to be a vehicle for the jokes to come (in many ways identical to a Pratchett novel).

I felt if you could combine the genre conventions of Noir with the strong juxtapositional imagery of DN and the hard-bitten attitude of Thief (and its central motivation about stealing things for profit) you could have a highly memorable take on the FRPG genre.

As I said in my introduction a lot of cities are essentially metaphors for the modern urban experience either satrised or idealised. The Greyhawk described in the book Greyhawk - The Adventure Begins (reviewed last issue) is in many ways a modern city with magic replacing technology. They have magical street lights, a democratic oligarchy of the bourgeois; rather more republican than a ruling aristocracy although the decaying nobility are retained for flavour in the form of dilapidated gentry and antiquated noble families. The city is divided into distinct sections with the slums and ghettos clearly divided from the more up-market sections of the city by the middle class and foreign quarters.

While I am sure that this model of a city has numerous individual medieval precedents I do think that it more a description of a modern view of an idealised modern city. In my search for a replacement Los Angeles, San Francisco or New York; Greyhawk has several key tenets already present. It has strong ethnic divisions with associated geographical locations. It has organised crime in the form of the Thieves Guild. It has a well-organised city bureaucracy that is prone to corruption. It has a physical and distinct divisions between the rich and poor. It is a city where magic can banish the darkness from the streets but people still have to sleep in the gutter. Greyhawk's Slum and High Quarters are equivalent to L.A.'s Compton and Hollywood Hills.

Characters able to move through the different strata of society are the equivalent of the Noir PI's moving between the nouvelle riche of rich speculators, businessmen and actors and the underworld of pornographers, blackmailers and the mob.

Greyhawk was created for the AD&D system so the obvious choice is to go with that if we are going to have any rules at all. I had two problems with AD&D: one I felt uncomfortable running the system with experienced AD&D'ers as the game could devolve into running rules arguments. To my mind so much of AD&D makes no real sense that it is pointless try to rationalise and justify the rules. The traditional answer "house rules" would mean a mind numbing waste of my time pouring over the AD&D extracting the best and getting rid of the rest. I did not want to spend time I could be writing the adventures and plots wading through the morass that is AD&D and then wasting gaming time explaining why such and such as spell works in the way I say it does. As it was even rejecting AD&D there were a lot of "in AD&D this works like this" comments that were annoying enough on their own.

Secondly I did not think that the AD&D system could really do the genre justice. AD&D has a lot strengths, particularly in the skirmish wargame field from whence it grew. Where it fails in what might be described as "skills heavy" games. Playing a detective means lots of interacting, keen observation, bluffing and deducting. So of that is pure roleplaying making the system irrelevant, some of it has to be system based though. Imagine a situation where a killer has exited a room just ahead of the party you could describe the room in a lot of detail and slip a mention of the curtain flapping in the breeze to see if the players rather than the characters get the reference and investigate further. Alternatively you can just describe the room and tell the players that the window is open if their characters have a look round. Unfortunately that does not really feel like "detecting things". The best answer to my mind is to include strong description of important locations to allow the players to tax their minds somewhat but to always allow a skill check so that the character might pick up

The best detective games I have ever played have been for the Call of Cthulhu (CoC) roleplaying game. Since CoC is based on the Runequest (RQ) rules system it seemed the logical thing to try to combine the fantasy magic and combat element of AD&D with the easy and detective based CoC skills system.

The RQ system is really simplicity itself; skills are given in percentages. Skills are then rolled under on d% for success. The skills are fairly broad - or at least are not specialised. Attributes can be multiplied by five (they are in the AD&D 3 to 18 range for historical reasons) to give a percentage and that is pretty much that.

To offer an example: if a character hears the name of a god and tries to remember any legends connected to the god they might roll a General Knowledge skill with a minus 20% penalty or their full rating in a more suitable skill such as Theology. In the window example given above the player might have to roll once to notice the open window and if the player fails to understand the significance of the window the GM can ask for an Idea roll (which is based on the character's Intelligence expressed as a percentage) that provides an out-of-character hint - or more accurately perhaps the character understands the situation despite their player.

One of the biggest problems with CoC is that it is hard to create an all-rounder

type character. I should have remembered this and noted some of the solutions to this problem that the Fifth Edition of CoC offered, applying these to the RQ system. As it was I feel straight into this problem head first all over again.

Noir heroes tend to be fairly experienced and capable types. They usually have a career as a policeman under their belt and normally have served in the Army, possibly having even fought in one of the World Wars. RQ by default spits out utterly inadequate 16 year old characters into the world. This imbalance is absolutely one of the things that caused immense problems in producing the right atmosphere in the game.

Instead of being experienced and jaded observers of the world the characters were often bumbling and incompetent. Not because of the players necessarily but because the rules couldn't translate the perceptions of the player's characters into the simulation of the world. They were conmen who couldn't sell ice to a man dying of thirst.

I do not think the system was the wrong system. On the contrary I still have not encountered a system as good as RQ for playing a detective style game swiftly and consistently. The percentile system is easy to grasp. The combat system is very detailed (perhaps too detailed for a conventional fantasy romp with its normal dependency on lots of combat) and handles the required knocking outs, duels and throat cutting admirably.

What I should have done was upped the characters Skill Points but forced them to spend the points in one or two "packages" akin to CoC's "Careers". This would probably have produced skilled yet balanced and rounded characters.

In the ongoing game of course the remedy was not so simple. I have decided to put the urban side of the game on hold while the group explore more conventional dungeon and wilderness games. Hopefully the characters who return from these adventures will be exactly the kind of characters I was looking for at the the start of the game. Not only that but the feel will be all the more authentic for having played through the required history

.

Noir as a term is widely applied beyond simply detective movies based on American novels written in the Forties about private eyes in the Twenties and Thirties. The term applies as much to the visual imagery as it does to the plots and the characters. The stories may be dark with few redeeming motives but the films themselves took this metaphysical darkness and transformed it into a more literal of estrangement.

Mysterious figures lurk in darkened alleyways, silheoutted strangers in a darkened city made inhabitable only by the power of electric light. In many ways Noir films harken all the way back to the age of fireside tales where gods and monsters lurked just beyond the ring of light from the campfire.

Trying to convey a visual style verbally is tricky but I felt if it was to be a true Noir game then it had to have a different feel and when the players put together their own internal story it would be a little more grimy and dark than the normal FRPG.

Essentially I came up with two ways of doing this: the obvious symbology of vamps and trenchcoats the visual trademark of Noir and secondly by trying to replicate the way that the original Noir novels read.

I am not going to say much about the first as I feel it must be quite obvious. Trenchcoats can be substituted for robes slicked with rain, the police are the city watchmen and beautiful women are beautiful women wherever and whenever you go. All Noir staples can be converted into FRPG equivalents, after all most FRPG backgrounds are based more on our own world and times than those of the medieval period many claim heritage from.

In terms of the latter the way a GM chooses to describe the game world can have a strong impact in the way the players respond to it. The Noir prose style is often characterised by a terse compact style. It is not given over much to lengthy descriptive passages. Emulating this is fairly easy. Think about your locations before a game starts and try to eliminate anything that is purely atmospheric or colour from your descriptions. For example you may know that the curtains in a certain room are purple but unless this is some kind of clue do not both to mention it unless the players ask.

This of course does not mean a return to the classic style of "you are in a ten by ten room". Descriptions need not be utilitarian and basic, simply short and sharp.

Another technique that seemed to work out was reversing my normal practice of giving every NPC a name where possible. For the Noir style games only the "important" characters were deemed worthy of a name. The bartender or the butler would simply be "the bartender", "the butler". This kept the game flowing as the group did not have to persecute "the beggar" (for example) just to see if he were a spy.

Another aspect of Noir is the lack of "dead time", even the main protagonist's introspection is limited to the case currently at hand. Any actions that a character wishes to undertake that are not relevant to the job in hand should be resolved quickly without too great a detail. Any time the group are uncertain as to what to do next then the NPC's should seize the initiative. Common events are a body turning up (possibly someone the group have met but have not had a chance to question in depth yet), a visit from one of the suspects or alternatively the authorities.

Noir is strongly narrative driven and character development and interaction often takes a back seat in these style of adventures. The point is to keep the plot moving.

My initial experiments in FRPG Noir were, at my own confession, far from perfect. The scenarios I devised were probably fit for the job from a story and plot point of view but as mentioned the characters were probably a bit under-powered for the job. It is important that the PC's are underdogs but that does not mean that they should be underlings. Since I intend to try and write up some example scenarios for the next issue I will live a discussion of writing Noire style games until then.

Since the group are often weaker than the collective abilities of their opponents the brawling element of most FRPG's will be less productive in the Noire style game. Generally the protagonists are expected to out-think rather than out-fight the opposition. This is particularly true where a general atmosphere of corruption and betrayal (such as permeates Greyhawk) means that the group cannot rely on the authorities or even their own nominal allies.

Since this is something of a sea change in the way most FRPG's are played I think the GM has to ensure that they signal to the players that the aggressive approach is going to be less productive than normal. This can occur in game (a warning but non-fatal beating by the villain perhaps) or simply via out of game conversations. I would prefer the former but it really is a style thing.

Despite this I am going to stick to Noire. It was a far from abject failure - it did have its own distinct flavour. For one thing the PC's were far from all-conquering heroes that commonly populate FRPG campaigns. They seemed frail and vulnerable and for the most part far more convincing human beings with desires and failings.

Putting the Noire spin on Greyhawk also helped revitalise the setting for me. I felt that it had become blander in its recent incarnation but turning the focus of the game to look at the city from the bottom of the social heap made it a lot more interesting for me as a GM.

And did Greyhawk become a character in the games as I had hoped? Probably not completely but there did seem to be a love-hate relationship between the characters and the city. They feared for their lives if they stayed but were often afraid of what would happen if they left. It was a token success but one that I would like to expand on.

Due to the fact that this issue is slightly more space limited than normal I do not quite have room for the article planned. Instead I will just lay out a rough sketch of where the series is going in the next couple of issues. Having established a few categories of city and determined the kind of geographical locations these cities are best suited to I would like to progress in a historic frame. The city having been founded (perhaps unwittingly) by a group of people moving to an area now must grow. To do so the first communal buildings must be put down, after all communal buildings are what distinguish a town from a village or a hamlet.

In the case of the Defensive city this may be a ditch, hedge, palisade or even fully blown stone walls with attendant turrets and towers. For the Trade City obviously the first priority is a marketplace. The Religious and Precedence Cities are usually founded around an existing feature so the core of their construction is usually already fixed and but requires formalising. Temples and rebuilt civic buildings might form the core of this regenerated city.

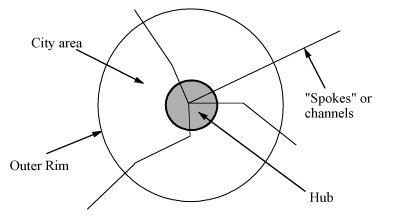

From these examples it seems that the best way forward for the series would be to concentrate on each of the city types in turn. To do so though I would like to introduce an abstract model of a city based on one that is probably already familiar to those of you who have taken any kind of basic geography course.

Of course normally the hub is called the CBZ and the outer section is referred to as the suburbs but both of these developments are essentially far later than the Renaissance period that usually marks the upper boundary of the FRPG genre.

The model is made up of abstract zones that will hopefully make it easier to describe the development of the various city types over later articles.

The Hub of the city is the true Heart of the City

. Often it will be located in the geographical centre of the city but the reason for abstracting the model is that I do not want to get involved in questions of urban geography or why things are placed where they are yet but rather I would like to concentrate on what is located there.

The Hub of the city is made up for the most part of the key civic and commercial buildings. In most early cities the distinction may very well be blurred. For example city granaries may be built and run by the city's government but will almost certainly be filled with the produce of private farms.

The Hub is where the city's politics and major business is conducted; it represents not only a geographical intersection but also a social intersection of community activity within the city. Town Halls, City Councils, Guild headquarters, markets and temples. Most city FRPG adventures begin and end in the Hub because not only is it a magnet for power, influence and authority it is where the business of the urban dweller is done. Either literally in the form of commerce or in worship or in the conduct of city politics. The decisions and actions taken in the Hub ripple out across the whole city effecting every part of its everyday life.

My conception of the Hub corresponds very heavily with the Italian idea of the Piazza or the large city square that served as a marketplace, debating hall, execution platform, gallery and simple gathering place. An inclement climate further north in Europe means that an open air plaza serving many functions is impractical but the idea has remained with important buildings such as the courts, churches and council offices all facing onto and sharing the same square.

When imagining what the Hub is I would say the easiest thing to do is to imagine a well paved square with all the key buildings of secular and spiritual life facing onto it. That is the Hub of the city.

For the moment there is not a lot to be said about the City Area. It is clearly the area of the city that is not considered part of the Hub but is not suburb or farmland. Its makeup though is highly varied including commercial and residential properties. There is no difference in this model between slums and silverworks.

I will cover the idea of splitting this City Area into a number of "Quarters" in a later article in the series. For the moment the only thing I want to point out is that locations placed in the City Area rather than the Hub indicate a certain lack of prestige. For example if a merchant has his home in the Hub then they must be wealthy and probably powerful. A home in the City Area does not necessarily mean that an individual is not as rich as their Hub dwelling counterpart but does indicate that in terms of politics and power they are removed from the heart of decision making and influence.

The Outer Rim is marked on the diagram because while some cities blend into their suburbs far more are protected by city walls or other fortifications. There is not merely a social or geographical boundary between the two areas there is a physical one as well.

A city not strategically located or importance to its rulers had to be very wealthy to afford city walls as the cost of raw materials and the number of skilled and unskilled workers involved was high. The completed result though was one that displayed a clear status.

City walls also often indicated certain social rules - not least enforcing the outsider-insider divide. Those inside the walls belong, those outside do not. As cities grow they frequently "burst" their walls. Those inside the original walls clearly have more of a history within the city that latecomers living either outside the walls or inside newly raised fortifications.

The Religious City also might use internal city walls to indicate areas of particular sanctity. Those places that should be hidden from the eyes of unbelievers or the lower orders of the religion.

The Outer Zone marks the territory in which the land moves from the more or less unreformed wilderness to the start of urban construction. The Outer Zone is rarely well defined but in most cases peters out gradually as wilderness turns to isolated buildings and cleared land and then again into more elaborate and densely packed urban construction.

Usually the Outer Zone never features in an FRPG game; you travel to a city on a road and the game continues when the party is safely arrived at the Core. If it does appear it is usually regarded suspiciously from behind a wooden palisade as attackers stream over it to lay siege to the city.

In all honesty the probable reason for the exclusion of the Outer Zone is partly its nebulous nature. In the early city it is made up of the farmsteads or allocated land outside the city walls or so on. Later on it becomes the location for buildings that need cheaper land, covered with the creeping sprawl of urbanisation. At this point you are faced with the simple fact that suburbs (as most who dwell there will admit) are boring. They are cheap because they are far from the powerhouse of the Core but this also leaves them isolated.

For the rest of the Heart of the City articles we will most assume that the Outer Zone is made up of farmsteads and land that actually feed the city. In amongst this may be small residential hamlets

, manors and noble estates but essentially the Outer Zone is the often neglected but never the less vital rural heartland of the city.

Spokes are abstract representations of the routes and flows of traffic (both people and goods) through the city.

In the proto city that is still little more than a town the spokes might be nothing more than rutted dirt tracks while a Trade city might quickly move to straight flat paved roads that lead right into the figurative heart of the city.

The number of Spokes a city has is an important indicator of certain properties of the city itself. A city with a large number of spokes relative to its size is easy to navigate and will rarely be congested. It is also easy to supply but correspondingly difficult to defend as there are many routes attackers may use to take the city. For this reason Defensive cities will often only have a few Spokes.

Each Spoke can be considered to possess a certain measure of quality. This quality is made up of such factors as how wide the passage is, how well maintained it is, the quality of its engineering and craftsmanship, how straight it is and so forth.

Spokes facilitate not only travel from outside the city into it but also between the Inner and Outer Zones.

When writing this series I have tried to keep in mind Paul Mason's advice that the city in an FRPG is not so much the impersonal result of economic, social and geographical forces as yet another NPC in the game with its own distinct personality.

In that respect I think this particular installment in the series is something of a rather serious failure. What I hope to have done instead is spend some time here creating a framework in which various cities can be analysed and a way to break down a city and examine its components.

One interesting thing that can be done with this model is to overlay on the traditional FRPG city map and see that for the most part it does seem to be a description of city that seems to apply regardless of culture, society or history.

Next issue I will try and analyse a few example cities and start breaking down the City Area into more detailed components.

Thank you for sending me another interesting issue. Starting from the back, I would appreciate keeping a hard copy version. Whether it is related to work, age or something else, I just don't keep going back over electronic material again like I do with printed stuff. Your mention in the reviews of Oerth Journal is a case in point; an excellent zine, but one that I cannot concentrate on giving the time it deserves. Demonground is a similar example. If cost is the issue, could you not charge for the first 40 as well? If you were to not take subscriptions, but simply on an ad-hoc issue basis, that would negate the need to carry out book-keeping.

Highly unusually, I agreed with your Comment completely. The one thing that you didn't add was that it tends to be these same names producing the same dreary stuff over and over again. I noticed this particularly, when I happened to have another look at my last copy of Valkyrie [issue 17] and the same people were all there, spouting their same "editorials". The writer's merry go-round of jobs for the boys does not seem to be related in any way to the quality of many of their scribbles, nor the regularity with which the periodicals they write for disappear with subscribers' money. It would be nice to blame the lack of different games, new scenarios and richer source material on these characters, but I guess that you are correct and they are simply part of the great Capitalist machine of deadlines, cost-cutting and profit.

The Heart of the City perhaps lacks being complete within the one issue. Given Carnel's release schedule (and this isn't a criticism), one tends to lose track of the arguments, and - more importantly - can hardly wait 6 months between issues when designing a city for use in a particular game. Overall, it is looking good, and I am enjoying it. I am not too sure that a little urban geography and/or sociology is not missing somewhere along the line, but I think it fairer to offer detailed comments when the piece has run its course.

The Secret of Phillip's Farm particularly interested me, for I also have that issue of The Wanderer, and re-wrote the scenario for my old C&S campaign. Yours is far better I hasten to add. That and Tales from Sylvania seems to nicely belie your claims to be a software zine, since the whole issue was pretty solidly either direct scenario material or discussions on how to run more realistic campaigns. I also wonder whether you are going to become an "official" WFRP zine at this rate! Your change of heart over the The Secret suggested to me that you might like to consider Gemini since I think that your Dark Influence matches their Darkness in intent. I was also a little puzzled by your view on orcs. Whilst the reason for their yellow skin intrigues me, to have a genetic stooping coupled with superior bowmanship seems highly peculiar at first glance.

With regard to the Monkey's Place, your reply to my comments upon orcs was not far from my own intention. I need to be clearer! I am not suggesting that orcs rely solely upon inherited assets, but that they do have a treasury incomparable with our own history to draw upon. I accept the existence of artisans, but I see them as lesser goblinoids for the reasons I stated. I have two problems with your and John Foody's discussion of orcs as Mongols. Firstly, I have concerns with the portrayal of the Mongols as inhuman monsters. By modern standards, they might have been barbarians, but so were the purportedly civilised Europeans. Orcs as Mongols need not necessarily fall into a racist trap, but it is there. My second problem within WFRP - which was the location for the original discussion - is that the Mongols already exist as the Hobgoblin Mourngols. In any event, I look forward to the article. Non-humans have never really been well covered by FRPs, with the notable exception of Gloranthan trolls. Do you remember those Mayfair products from the 1980s...?

I don't want to bore everyone further with the "dipshit" issue, and for what it is worth, I have no problem with you printing such comments should you receive them. My disapproval of the comment would, by its nature, lie with the originator, and not the messenger. Since I don't recall meeting Paul Mason, or communicating with him, I find it difficult to rationalise that I misunderstood a joke. To say that someone is not worth bothering responding to, and that they are like other such dipshits, is something I do not find remotely funny, nor do I have a context where I could see it as such. In any case, since Robert Clark also failed to see the joke, this probably damns the both of us as ignorant and irrelevant in Paul's eyes. Actually, I have not met anyone who did see it as humorous, yourself included. As to my point, I really don't want to belabour it, but I am not saying that one shouldn't try and understand other cultures, or play games set in them, but that there are definite limits to them. It is grandiose claims that (for example) I can realistically be an outlaw from the Water Margin in a game, that I find untenable. For example, I have read Han Yu - who apparently can create beauty out of ugliness - and I have read Tu Fu. I think they are lame. Now, this could be because Paul's original comment was true. I think it more likely that it was because I read them in translation, and that I know very little about Chinese culture, philosophy, sociology, history, politics and economics compared with my knowledge of (say) Germany. So, if the majority of people who play Paul's game are from western Europe and the United States, I am not convinced that they (we) will do much more than play as they (we) would any other generic RPG. Paul's points upon history are perfectly true, except that this is precisely my point. In certain moods, I would actually claim that there is no such thing as a "fact", that they are all personal opinions to explain what an individual perceives. For these reasons, I am not impressed with most historical FRP supplements. They simply do not work, neither giving a complete culture nor serious analysis on how to use them in a game situation. I was reminded in a conversation recently of Viking supplements, which are all pretty universally dire. Even the great Graeme Davis, who manages to include both rules and context in every single one of his near infinite scenarios and backgrounds, failed to portray Vikings either realistically or as a useful game culture in my view.

Simplistic example, and (sarcasm coming up) I have no doubt that early issues of Imazine covered all this, and that we are all pretty stupid for being so far behind. Let us take the case of a white Englishman living in modern China. Even if he speaks perfect Mandarin, or whatever dialect is appropriate, and knows exactly how to act in any situation, he is never going to be treated by the locals as a local. He will always be treated differently as a westerner. Rules will be relaxed for him. He can never understand what it is to be a local. Now, say he stays there 50 years and becomes accepted, what is likely to happen when he returns to (say) London. It will be another culture shock. He will be so used to China, he will not be able to relate to London, until London begins to replace China. The two cannot co-exist in their pure forms. More sophisticated arguments on this vein are the accepted academic traditions for anthropologists and sociologists to which I was referring.

Okay, that is a ridiculously simple example to try and explain the basic point. The point is that given no-one in the UK is educated in anything Chinese I think the chance of a player being able to give a twelfth century Chinese outlaw a realistic play are doubtful. Even the British Museum has a pitiful twelfth century collection, compared with its other departments - and everyone knows the basic context of an Egyptian mummy. That is not to say we should not try, nor that we shouldn't play Outlaws. I just do not think that Paul should expect what I had read he was expecting people to get from the game. And if he cares to re-read my comment in issue 12, I am applying the original statement to myself. And, for what it's worth, I cannot even be vindictive and say the game stinks, because it doesn't. I actually think that it is very good.

Two comments that I will flag as sarcastic/humorous. Firstly, yes, I am aware of the revisionist Richard III historians. Yorkist liars the lot of them. We all know that Richard was a murderer and regicide, illegally trespassing upon the throne. Secondly, I am sure that we are both pleased that Paul will allow you to print and myself to write items for Carnel. Very gracious of you, Paul!

I will respond to "your" Zine Reviews, though obviously I have yet to see most of the material. I agree about the APAs. They have always struck me as a hangover from the 1970s. Modern DTP is so simple that I really don't see the need anymore, and the Internet with free web space for all, simply reiterates that. I will buy the SLA zine, as much as that the game needs support, and the fan material within it - provided it isn't complete crap. "Your" review suggests its pretty good. Whilst I write for Warpstone, I hold no editorial or ownership remit, so I can be pretty independent in my views upon it. Looking from the outside of the entire Hogshead/WFRP situation, I agree with The Man and A Moose. With Warpstone, I think Hogshead gains what it has palpably been unable to deliver since its take-over of the system - a regular product release. In addition, it has also failed to release a single of "its" issues to that schedule. Sure, we are all grateful that Hogshead and James Wallis saved WFRP from oblivion, but that gratitude is getting a little long in the tooth now and we have seen precious little new material, and even less good material judging by the reviews Dying of the Light received. As for the size of John Foody's contributions, I see no problem with it as long as it remains of high quality. Writing an article for one's own publication is not necessarily wrong. I do not believe vanity publishing within RPG's is the equivalent of writing the same in academic journals, and I think it should not use the term. The two are different. I doubt any RPG magazine has the same external review standards as academic journals, but I can speak from both sides and I would say that Warpstone is pretty thorough at its review standard. For what it's worth, when I wrote the article in the last piece, I thought you were thorough too. In any case, and back to the point, I think it is a cheap shot and an unfair implied criticism upon John to use the issue - and I think I would include you within this, as I recall a similar comment by yourself in an earlier issue. All that matters at the end of the day is that articles are either good or at least worth the cover price. Where it has failed in other zines, is where the quality was not there. In addition, I am much more against the "jobs for the boys" I mentioned in response to your Comment, and the same garbage that gets produced over and over again there. Anyway, I reckon issue 12 was unusual in this regard, but even so - reviews aside - only the scenario and one short article was John alone. That said, I would not rate issue 12 as one of their best either, though I am not sure that this does not strengthen the above argument. Finally, to contradict everything I have just said, I did note some time ago that every single scenario was a Foody creation and I have already promised a scenario before issue 20, just to prevent his having to go an entire twenty issues on his own. Mind you, when I promised, I was not expecting it to actually stay around that long!

In summary, thanks for another issue, and particularly for having a functional RPG issue. I hope we can continue in the vein that you turn out an issue, send it to me, and I'll gabble a few pages of (dipshitty) commentary at you in payment. If only the rest of life was this simple...

Tim Eccles

Sounds a good a principle to run a business as any.

I am not really going to comment on M&M's reviews as there was a reason for spinning that section off to others (although I might re-enter the lists in a couple of issues with a joint article). The only thing I will say is that I enjoy John Foody's scenarios immensely but it only takes someone to point out the credits on the content pages to realise the man is doing a grand job of work, one bordering on the Herculean.

I see what you are saying about the Mongols, strangely enough as I was doing a bit of reading about Orcs I came across a good quote from J.R.R. Tolkein about the origin of his Orcs as debased carictures of Mongols. It is not totally clear to me whether he regarded Mongols as sub-human or whether he chose them for the way their European contempories saw the invaders.

Since this vision of orcs is about equal for me with the GW idea of green orcs I tend to think of Orcs as being of both colours, brown and green, depending on their geographical origin. Half-orcs I always think of as being brown or yellow. Goblins on the other hand I always think of as green. It is all quite curious when you think about it.

You are right to pick me up on the stooped archer

. What I meant initially was that Keenan was a good archer whose upper body was out of proportion with his lower body. The two were initially unconnected in my mind but then connected in the text. Since writing the scenario though I did discover that lifelong archers do have a slightly different upper body structure from the norm. Their bones are thickened slightly and the larger the bow the more force you need to draw it, hence a more toned upper body and arm physique.

You should feel totally at liberty to choose either idea of course, or ignore the whole thing as it has very little bearing on the game overall.

I think you are probably right about The Heart of the City but I am not at all sure what should be done with it. For the moment I am trying to concentrate on smaller more frequent carnels, perhaps that may help a bit. I do not intend to let another year go by!

All of which brings us to the start of your letter. The problem with the subscriber list reaching the heady heights of the over-forties was mostly the cost but partly because the subs themselves were mostly very quiet and it was not clear whether people were reading and enjoying the zine (and therefore presumably would like to continue to receive it) or whether they were continuing to receive a zine they did not want or indeed due to changes of addresses were not receiving the zine at all.

Since the cull has brought the list down to about twelve people I now slightly regret agreeing to put the zine on the web when I could have concentrated on producing a good paper zine. Something I find more satisfying personally than the webzines I am aware of. What I needed to do is cull the subs list more closely and simply let people who lapse decide whether they wanted a copy or not by forcing them to contact me.

I am slightly annoyed by the web's idea of something for nothing. I get quite a few queries about carnel and Tetsubo via e-mail. When I respond and it is made clear to these people they are not going to be e-mailed a copy this instant quite often they do not even have the decency to reply and say they are not interested. Instead you are left dangling, a virtual dropped call.

Since the cost of the zine is simply an SSAE (and more often than not I make up the excess postage out of my own pocket) I simply do not understand why people feel they cannot make a decision one way or another.

Anyway, we shall see what happens with the web idea. Rest assured though that there will always be a paper carnel.

Chances are that you are already familiar with The Dumas Club

(TDC) from its film incarnation: Roman Polanski's Ninth Gate. I must admit that I picked it up because I was intrigued by the Johnny Depp jacket but after reading a few pages at random I had to have it.

Spanish writer Arturo Pérez-Reverte's prose (translated by Sonia Soto) is fantastically sharp and alluring, strongly literate it is both clever and entertaining. While occasionally flying off on whimsical notion overall the text is sharply focussed and hard-edged. It assumes the reader is not an idiot and unlike quite a few British writers at the moment it assumes that you are more interested in the narrative than the author.

The story revolves around Corso, a mercenary of the book world

, who has the task of trying to discover the authenticity of a seemingly unrelated manuscript and a Medieval book called The Nine Doors

. There are only three copies of The Nine Doors in the world and Corso thinks he may have one. As he sets out to prove this though the other owners start to die in suspicious circumstances and their copies are despoiled. Could the culprit be a stranger who seems to be seeking the manuscript he has?

In many ways a traditional thriller TDC is one of those books that pulls you from one page to the next, slowly engrossing in the tale while the rest of the world simply slips away. Plot and sub-plot merge but the truth remains hidden until the end.